The construction of Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) has been a source of immense pride and hope for the Ethiopian people. For years, they have been working tirelessly towards this project, with the aim of generating much-needed electricity to power their country’s growth and development.

And now, as experts predict that the GERD dam will be a potential boon for all, the Ethiopian people can’t help but feel a sense of excitement and anticipation. They know that this project has the power to transform their country’s economy, create job opportunities for their citizens, and provide clean, renewable energy to the entire region.

But it’s not just the people of Ethiopia who stand to benefit from the GERD dam. Experts believe that the project could have positive impacts on the entire region, from Egypt to Sudan and beyond. By harnessing the power of the Nile River, the GERD dam could potentially provide a new source of energy for millions of people, help to alleviate poverty, and promote economic growth.

Of course, there are still challenges to be faced along the way. Negotiations between Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan over the distribution of Nile water have been ongoing for years, and tensions between the three countries have occasionally flared up. But despite these challenges, the people of Ethiopia remain optimistic about the future.

For them, the GERD dam represents more than just a new source of electricity. It represents hope for a brighter, more prosperous future – not just for themselves, but for the entire region. And as the project moves ever closer to completion, that hope only grows stronger.

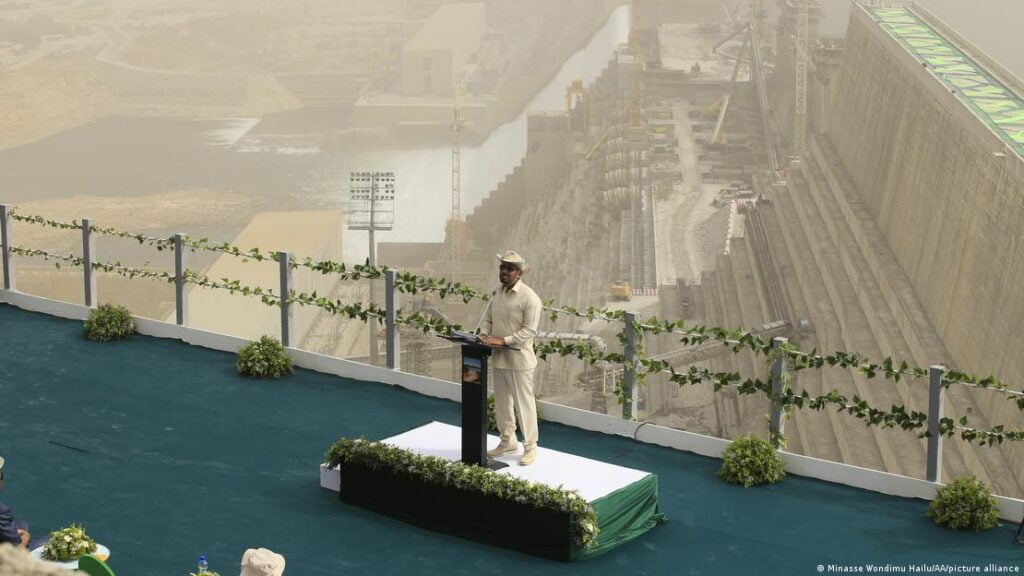

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, or GERD, has been dogged by controversy ever since construction started on the $4 billion (€3.6 billion) mega project in 2011.

Above all, the two neighboring downstream countries of Egypt and Sudan have expressed worries that the dam could lead to reduced water flow in the Nile River, causing increased water scarcity — a major issue in a region that suffers acutely from droughts and negative effects of climate change.

Now, 12 years on, Ethiopia’s Office of National Coordination has announced that the hydroelectric power dam has been 90% completed.

For Ethiopia, the dam will make a huge difference. The government expects it will generate up to 6,500 megawatts of electricity, doubling the annual national electricity output. This will enable 60% of the population that is not yet connected to the grid to gain access to reliable power.

Ethiopia’s neighbor Sudan, which draws two-thirds of its water supplies from the Nile and regularly suffers from massive flooding during the rainy season, had first criticized the project from the start. Now, however, it seems to have changed its view amid hopes that the dam will help to regulate the annual floods.

In January, Sudan’s de facto leader, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, told Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, that the two countries were “aligned and in agreement on all issues regarding the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.”

Egypt, which was also an early critic of the project, has, however, not changed its mind, maintaining that the dam on the Blue Nile, the River Nile’s main tributary, will jeopardize its water supply.

Around 97% of Egypt’s population of 106 million people live along the River Nile and depend on it as a source of fresh water. There is also a deep-lying emotional aspect at play in the country’s criticism of the project, as the river has always been considered Egypt’s lifeline.

In mid-March, Egyptian Foreign Minister Sahme Shoukry told local media that “all options are open, all alternatives remain available” in the context of the dam’s upcoming completion, which is being closely followed by Egypt.

Egypt’s warning came despite the fact that it has found a solution to make up for the loss of water caused by the filling of the GERD water reservoir, which started in 2020: Egypt has directed more water from Lake Nasser, the water reservoir of Egypt’s own hydropower Aswan High Dam, into the Nile.

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam: A never-ending saga

From corruption and mismanagement to a looming diplomatic crisis: Construction on Ethiopia’s mammoth dam has been far from smooth sailing.

Image: DW/M. Gerth-Niculescu

A concrete colossus

At 145 meters high and almost two kilometers long, the Grand Renaissance Dam is expected to become Ethiopia’s biggest source of electricity. As Africa’s largest hydroelectric power dam, it will produce more than 15,000 gigawatt-hours of electricity, beginning in 2022. It will source water from Africa’s longest river, the Blue Nile.

Image: DW/M. Gerth-Niculescu

The outlook so far

With more than 50% of Ethiopians still living without electricity, the government wants the dam to be up and running as soon as possible, so tens of millions of residents will be able to access power. The first of a total of 13 turbines is due to be operational by mid-2021.

Image: DW/M. Gerth-Niculescu

A long time in the making

Construction on the current dam began in 2011 — but the site was identified between 1956 and 1964. The coup of 1974 meant the project failed to progress, and it was not until 2009 that plans for the dam were resurrected. The $4.6 billion (€4.1 billion) project has consistently been the source of serious regional controversy, with its plan to source water from the Blue Nile.

Transforming the landscape

In a few years, this entire area will be covered in water. The reservoir which is needed to generate electricity is expected to hold 74 billion cubic meters of water. Ethiopia wants to fill the artificial lake as soon as possible, but neighboring countries are concerned about the impact this might have on their own water supplies.

Diplomatic deadlock

Egypt, in particular, fears that filling the reservoir too quickly will threaten their water supply and allow Ethiopia to control the flow of the Blue Nile. Ethiopia is insisting on having the reservoir filled in seven years. Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed met with Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi on Sunday, to discuss the matter.

No solution in sight

However, two days of negotiations between Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan in Washington over the weekend failed to solve the reservoir issue, despite the US stepping in to mediate. With no progress over the last four years, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed even called on South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa — and the 2020 chairperson of the African Union — to intervene in the dispute.

Back-breaking work

Amidst the heated negotiations, up to 6,000 employees are still working around the clock to get the dam completed by the deadline. The working conditions are not for the faint-hearted: In the hottest months, temperatures on the construction site can reach up to 50 degrees.

Project mired in corruption

Over the years, construction was also delayed significantly due to ongoing corruption and mismanagement issues. Last month, 50 people were charged with severe graft offenses relating to the dam, including the former CEO of Ethiopian Electric Power (EEP).

Military conflict off the table

Despite the criticisms still coming from Egypt, researchers now tend to rule out a military conflict between it and Ethiopia over the GERD.

“The window for any possible attack on the dam has closed, given the fact that the reservoir is nearly full,” Timothy Kaldas, deputy director of the Washington-based Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, told DW.

An attack on the dam at this point would result in massive flooding of Sudan’s Blue Nile River. “This is something that the Egyptians will certainly not pursue,” Kaldas said. Egypt and Sudan are regional allies.

Jemima Oakey, an Amman-based researcher of water and food security in the Middle East and an associate at the London-based consultant firm Azure Strategy, agrees. She told DW that “launching a militarized offensive, which Egypt lacks the economic resources and geopolitical backing to do, would be neither justifiable nor in Egypt’s interests, as there is also no guarantee that any conflict would leave its water situation improved.”

GERD’s regional implications

“The dam project in Ethiopia is an illustrative example of the extent to which national modernization projects and environmental dependencies are simultaneously reinforced by the constant threat of climate change,” Tobias Zumbrägel, a researcher focused on the impact of climate change on the Middle East at the Germany’s University of Heidelberg, told DW.

“We are longer just talking about a water problem, which is a major problem in itself, but we are also talking about the fact that an entire region is actually under threat of becoming more destabilized,” he added.

For example, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf countries have reiterated their willingness to back Egypt in demanding sufficient water supply from Ethiopia.

Egypt, however, has repeatedly accused Israel of working against its interests when it comes to the GERD, despite the otherwise solid bilateral relations between the two countries, which signed a peace agreement in 1979.

Israel and Ethiopia also have close diplomatic ties.

Scientific solutions

Researchers point out that there are political and scientific ways to settle the situation.

“Egypt’s and Sudan’s most pragmatic, cost-effective and peaceful option is to set up a data-sharing agreement with Ethiopia to manage the water flows from the dam,” Jemima Oakey told DW. Such an agreement could include guaranteed water releases during times of drought. “It would build trust, promote cooperation and allow for sustainable and careful multilateral management of the Nile’s flows,” she said.

However, since construction started in 2011, Ethiopia has repeatedly rejected such options, as well as other forms of political agreements.

Hagen Koch, a senior scientist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, in his turn, pins his hopes on a scientific approach. “Great benefits could be derived if Egypt’s Aswan High Dam and Ethiopia’s GERD were operated together,” he told DW.

“The GERD is located in the highlands; the Aswan High Dam is on a much lower altitude where temperatures are higher,” he told DW, adding that Aswan’s water reservoir Lake Nasser is also four times larger than the reservoir of the GERD.

“If you manage this sensibly and store more water in the GERD than in Lake Nasser, you will have lower evaporation losses, and thus both countries would have more water available for their respective hydropower generation.”

It remains to be seen whether by the time of the dam’s completion in 2024 or 2025 — depending on the amount of rainfall during the rainy season — any agreement will be reached.

Edited by: Timothy Jones