In Yemen, Houthi militias have used the corona crisis to violently chase out Ethiopian migrants across the border with Saudi Arabia. There they have been shot at by the Saudi border control. Now, more than five months later, hundreds of Ethiopians migrants are still being held in Saudi detention centers in dire circumstances.

‘These people have corona. Their lives are worthless. Let them die and don’t say anything about what happened to them’, is what an Ethiopian health care worker heard the Houthi militia man say.

The health care worker, a doctor who works in a local hospital in the north of Yemen, was instructed not to tend the wounded who had been brought in. An Ethiopian himself, he recognised their language when they begged for water. They had survived the attack directed on their camp, but were given no medical care, they died of their wounds, like pariahs. This was the statement the devastated care worker made to Human Rights Watch.

In April, dozens, perhaps hundreds of migrants supposedly died due to attacks by Houthi militias. Afterwards others supposedly died at the hands of Saudi border guards. This news circulated for some time amongst the Ethiopian diaspora.

Hundreds of migrants reportedly remain imprisoned in detention centres, where they suffer from deprivation. With the help of relatives and friends their cries for help have made it to the outside world.

Murdered at the border

Several of Kiros’s* friends and relatives were among them. He shared their story by telephone with MO*. They did what he himself had done three years ago: they travelled clandestinely to Saudi Arabia via Yemen, in a search for employment.

‘My neighbour was only 34 years old. He leaves a wife and two children in Ethiopia.’

Because of the corona pandemic, their trip was more complicated than they had hoped. They got stuck in the mountains of Yemen, close to the border.

‘Suddenly I received word that they had to flee from Ragu (Souq al-Ragu, ed.) Houthi rebels said they wanted no corona and that they should leave’, Kiros tells us. That was on the 17th of April.

‘Then, when they were about to cross the border to Saudi Arabia, they were shot at again. Three people I know were murdered by Saudi border guards’, says Kiros. Human Rights Watch subsequently confirmed these reports. Probably dozens more died at the border.

A few days later a large group of Ethiopians were finally picked up by Saudi border guards and transferred to detention centres.

By now, almost five months after the shooting at the border, Kiros’ list of victims known to him personally has grown longer. My neighbour was only 34 years old and he leaves a wife and two children in Ethiopia. Both children are under four.’ He has not yet found the courage to pass on the news to his family.

The young Ethiopian he is talking about, survived the trip through Yemen but succumbed to deprivation almost five months later, in one of the overpopulated detention centres in Saudi Arabia. ‘It was way too hot and there were too many people packed in together. He became ill but received no medical help. He finally died in these sad circumstances.’

Kiros doesn’t know where his body is. ‘We gathered together as Ethiopian migrants, here in the southern Saudi province of Jizan to mourn his death.’ The longer the crisis lasts, the more deaths we can expect, he fears.

The hundreds of migrants currently being held seem not to be able to count on any assistance from their own Ethiopian regime. The political crisis in their own country appears to be complicating their repatriation attempts.

Human Rights Watch and several organisations within the Ethiopian diaspora are calling on the international community to intervene.

From Ethiopia to Saudi Arabia

More than 30,000 migrants clandestinely crossed the Gulf of Aden this spring according to an assessment by the UN’s, International Organisation for Migration. Like Kiros, most of them come from the northern Ethiopian region of Tigray.

Annually thousands of Ethiopians cross the Gulf of Aden, via Somalia (specifically the autonomous region of Puntland) or Djibouti. Travelling via Yemen, they reach Saudi Arabia. The last of their savings is given to smugglers, in the hope – after the harrowing journey, of reaching the country where they believe they will earn up to seven times as much as at home.

In 2017 IOM reckoned that half a million Ethiopians were living in Saudi Arabia, most without documentation of residency. Initially the Gulf State had tolerated the presence of large numbers of workers providing cheap labour, even attracted them. After the Arabian Spring however, the kingdom was keen to drastically reduce the numbers of foreign migrants. It was concerned that revolutionary ideas would undermine the power of the monarchy.

Between 2013 and 2014 up to a 100,000 migrants were picked up and sent home.

‘Leading a clandestine life, with the limited freedom that entails, is harder than I had expected.’

In 2017 Saudi Arabia launched the ‘A nation which remains intact’ campaign. An amnesty period of 90 days was introduced in which voluntary returnees were absolved of fines and detention. Then a new and active deportation policy was initiated. It is estimated that some 380,000 Ethiopians have since been deported.

The regime in Ethiopia received a lot of financial support from Saudi Arabia over the past number of years and was therefore slow to protest the harsh Return Policy directed against irregular migrants. Migrant remittances to their families in Ethiopia also formed a substantial source of income. And so, many Ethiopians continue to be attracted by the Arabian Peninsula.

Approximately the same number of migrants therefore headed in the opposite direction towards Arabia over the past 3 years as were deported due to the active deportation policy. More than 300,000 are said to have made the crossing. According to IOM, in 2019 another 84,378 new migrants arrived in Yemen of whom 87% were Ethiopian. Without exception, they declared Saudi Arabia to be their final destination.

Kiros too had hoped that a life in Saudi Arabia would ease his financial worries. The reality however did not match up to the stories he had heard at home: ‘The restricted freedom that goes with being undocumented, is harder to bear than I had expected.’

‘It’s also much harder to find work.’ As an undocumented day-labourer, Kiros tries to earn as much as he can in the building sector. He manages to send money home, but earnings are highly unpredictable.

‘Sometimes you can’t even reach the food because you’re impeded by the chain on your foot.’

‘Many of my relatives and friends have been picked up and returned home. It’s just luck that I’m still here’, he believes.

Personally, he’s not keen to go back home right away. ‘But even if I did want to go, I’d be scared I might be held in a detention centre first for an undetermined period of time.’

Human Rights Watch formulated a complaint last year about the atrocious circumstances in those centres in a report: ‘We were beaten while chained by our feet. Sometimes you couldn’t even reach the food because of the chain. If you had the misfortune to be chained near the overflowing toilet, then the waste simply ran under you’, an anonymous witness has testified.

Stranded by COVID-19

Witness statements in the reports, the stories of deported migrants, the risks along the way: none of these have actually stemmed the tide of migration from Ethiopia. In 2015 a civil war broke out in Yemen. That too had little effect on the numbers of trans migrants.

Yet, since the war in Yemen, the risks have increased considerably. More than ever, people passing through the country were subjected to extortion and kidnapping for ransom. Most migrants questioned in the past, responded that they had not been aware that Yemen was at war.

In contrast to the civil war however, the corona crisis does appear to have an impact on the migration route. In January and February 9,000 migrants per month still continued to arrive in Yemen. Since March that number has decreased. In April an estimated 1,725 migrants arrived. For many their journey ended there.

‘Migrants are the scapegoats. They’re accused of spreading the virus.’

In July Christa Rottensteiner, head of IOM Yemen, warned that thousands of migrants have been trapped in the country since April. Already, 4,000 migrants have approached the agency in Aden seeking help to return home.

‘For over six years Yemen has been an extremely unsafe place for migrants’, writes Rottensteiner. ‘COVID-19 has made the situation even worse. Migrants are scapegoats accused of spreading the virus. This leads to exclusion and violence.’

20-year-old Mohammed testified to the UN Agency. ‘We had been walking for a long time, but I could go no further. I felt deathly ill. I told the group to go ahead without me. I fell asleep and, in the morning, I made my way towards a mosque. I stopped to drink water at a public fountain near a restaurant, but they chased me away. They shouted: “Corona! Corona!”’

Houthi attack

‘I fled with a group of 45 or so. Only 5 of us survived the attack.’

Kiros’s friends and relatives too were stranded in Yemen. They held out in the mountains in the northern region of Sa’dah, waiting till the coast was clear. Usually, this is a halting point, just before you come to the border with Saudi Arabia. Three years ago, I rested there too for a short period. But they’ve been trapped there for a while now.’

That same mountainous region has been taken over by the Houthi rebels who have fought against the regime in the capital city Sanaa since 2015.

In April Kiros received word from his contacts that the rebels intended to empty the migrants camp The Houthi rebel fighters said they wanted no corona and therefore we should leave’.

Eventually the camp was cleared violently, and dozens of Ethiopians were killed.

A pregnant Ethiopian woman, in transit with a young child, testified to Human Rights Watch: ‘There were more than fifty lorries filled with soldiers. They took a mortar, set it on the ground and fired. We all started to run. I fled with a group of 45 or so. Only 5 of us survived the attack.’

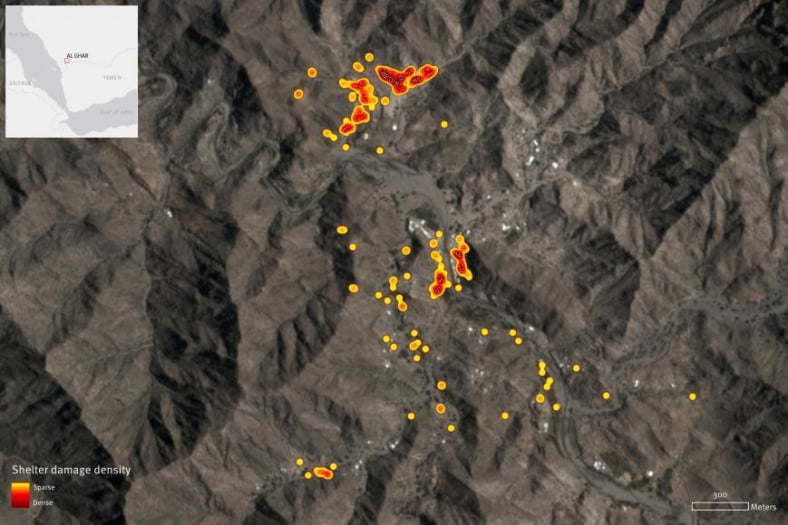

Using satellite imagery Human Rights Watch ascertained that the camps were subsequently destroyed. Those who survived the clearance were faced with a new deadly obstacle at the border.

‘No one should have to live this way. I can’t describe what we go through each day.’

At the Saudi Arabian border, they were fired upon from the direction of the border. ‘Three people I know well died there’, Kiros confirms. ‘They were killed by bullets of Saudi border guards.’

Survivors sheltered for five days in a riverbed close to the border. Eventually they were picked up by Saudi border guards. Men were separated from the women and children and detained in separate facilities. Families were split up. They were held in different places in Jizan Province.

Kiros and other family members continued to receive disturbing messages from the centres. Human Rights Watch also managed to interview several detainees by telephone. They testified about overfilled facilities, a shortage of beds and sheets, overflowing toilets, and an absence of medical care.

‘400 people are being detained in a space of approximately 150 square meters. We receive a daily ration of three small pieces of bread with a litre of water. The bread is not sufficient. There is a toilet. It does not work but everyone continues to use it. Many are sick. No one should have to live this way. I can’t describe what we go through every day’, says Desta*.

Terrorists in the eyes of the prime minister

‘The latest report was an audio message. They said they’d been brought to an unknown place.’

Just prior to the publication by Human Rights Watch, representatives of the Ethiopian Embassy visited a centre for women in the Jizan province. They registered pregnant women and women with children. 350 women and children were repatriated to Ethiopia.

The Ethiopian authorities are therefore aware of the situation and do collaborate on deportations from Saudi Arabia. Between April and the beginning of August more than 3,000 Ethiopians were forcibly repatriated from there. But except for the group of pregnant women and women with children, banished migrants are still in detention in Yemen.

Since the HRW report was published Kiros has had no more contact with his friends or relatives. ‘The last I heard from them was an audio message saying they’d been removed to an unknown place.’ He fears their telephones have been confiscated.

He is also concerned about the lack of support from their own Ethiopian authorities. Over the course of the past few months organisations within the diaspora sent several messages to the embassies of their mother country.

Prime Minister and Nobel Peace Prize winner, Abiy Ahmed, explained in a speech to the Ethiopian parliament on the 7th of July why the whole group had not been repatriated. ‘The risks are too high because we believe that some of them are trained terrorists. There are some among the stranded who form a threat. They are trying to re-enter the country using corona as an excuse.’

In Ethiopia, the strain between various ethnic groups had increased strongly over the past few months. Most of the migrants are from Tigrinya in the north. Although federal elections which were due to take place have been postponed, the regional government of Tigray plans to hold elections in September. The regime in the capital perceives this as a political provocation. The fear is great in the Tigrinya community that migrants will now additionally become victims of political unrest in their own country.

Human Rights Watch calls on the UN to intervene and request that Saudi and Ethiopian authorities collaborate to resolve this crisis.

*Names of witnesses have been changed in order not to endanger them.