By Bekele Atoma

BBC Afaan Oromoo

Having previously warned that Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed risked turning into an “illegitimate” ruler, Jawar Mohammed, 34, has now become the most high-profile opposition politician to be detained since the Nobel Peace laureate took office in April 2018.

An ethno-nationalist with a Facebook following of nearly two million, Mr Jawar is accused of being linked to the murder of a policeman during the violence which erupted last week after music star Hachalu Handessa was gunned down in the capital Addis Ababa.

His allies deny his involvement in the murder, saying Mr Abiy ordered his arrest to neutralise the popular opposition politician.

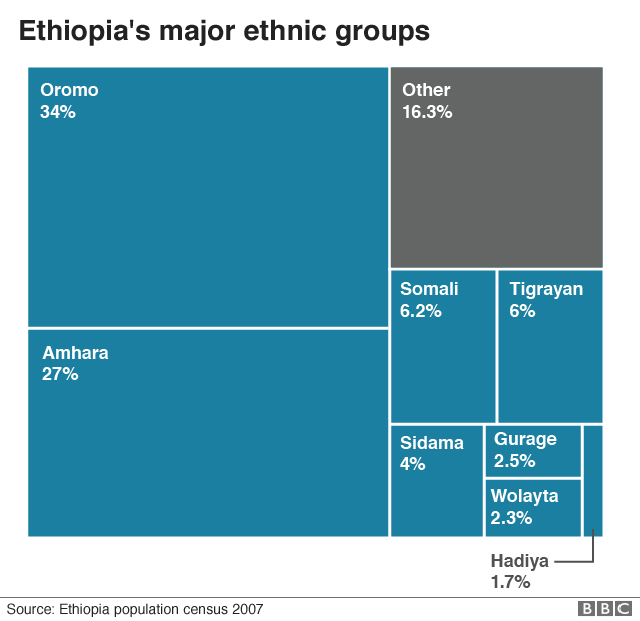

Both Mr Abiy and Mr Jawar hail from Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group, the Oromos, but have differed sharply over the future direction of Ethiopia since Mr Abiy took power in 2018, with a promise to democratise and unite the ethnically divided nation after decades of authoritarian rule.

For government supporters, Mr Jawar’s arrest was vital to help quell the ethnic nationalism and violence that they accuse him of fanning to derail the prime minister’s “coming together” vision, aimed at forging a new sense of national unity in the country of more than 100 million.

But for Mr Jawar’s supporters, his arrest showed that the prime minister had become intolerant of the 34-year-old’s alternative vision, which revolved around the federal state giving self-rule to Oromos and other ethnic groups in regions where they constitute the majority.

‘I am an Oromo first’

Born in 1986 to a Muslim father and an Orthodox Christian mother, Mr Jawar established his credentials as an Oromo nationalist in a 2013 interview with the Qatar-owned Al Jazeera television station.

“I am an Oromo first,” Mr Jawar – then exiled in the US – declared, adding that Ethiopia had been “imposed” on him.

His comments unleashed what Keele University law lecturer Awol Alo described at the time as a “political tsunami”, with people either passionately supporting him or harshly criticising him in a highly polarised debate that swept through Ethiopia and the diaspora. GettyWe’ve now liberated the airwaves of Oromia. We will liberate the land in the coming years”Jawar Mohammed in 2013

GettyWe’ve now liberated the airwaves of Oromia. We will liberate the land in the coming years”Jawar Mohammed in 2013

Ethiopian opposition politician

“I am an Oromo first” later grew into a political campaign, with the-then Minnesota-based Mr Jawar criss-crossing the US to rally the diaspora to oppose the regime back home and to win their “freedom”.

The campaign culminated with the launch later in 2013 of a satellite television station – along with social media accounts – under the banner of the Oromia Media Network (OMN).

“We’ve now liberated the airwaves of Oromia. We will liberate the land in the coming years,” Mr Jawar said at its launch.

As its then-chief executive officer, he turned the OMN into a powerful voice of the youth, whom he called “Qeerroo”, which literally means “young unmarried man” – a term first popularised in the 1990s by the-then banned Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) rebel group in its bid to attract recruits.

Having grown up in the small town of Dhumuga where the OLF had a strong presence, Mr Jawar often said: “I was born in the Oromo struggle,” as he recalled learning about the “oppression” of Oromos under the rule of emperors and autocrats alike.

Despite being the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, Mr Abiy was the first Oromo prime minister, while during the time of Emperor Haile Selassie, their language and traditional religion were banned.

A bright student, Mr Jawar left Ethiopia in his teens when he won a fellowship to study in Singapore in 2003. Two years later he moved to the US where he graduated with a political science degree from Stanford University and a masters degree in human rights at Colombia University in 2013.

‘Strategic blunder over Abiy’

As a university student, Mr Jawar distanced himself from the OLF he had revered as a child, writing in a blog that it was “broken beyond repair” because of leadership disputes and factionalism.

But he continued to rally the large number of Oromos in the diaspora to support the “struggle” back home, which gained momentum after mass protests broke out in 2015, forcing the resignation of Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn three years later.

When Mr Abiy first emerged as Mr Hailemariam’s potential successor, Mr Jawar warned that it would be a “strategic blunder” to give him the premiership, indicating a preference for current Defence Minister Lemma Megersa, whose political vision, Mr Jawar felt, was closer to his own.

But once Mr Abiy became the first Oromo to ever secure the premiership, the 34-year-old supported him, especially after he embarked on a series of reforms that saw the unbanning of opposition groups, the release of thousands of political prisoners, and the dropping of terrorism-related charges against exiles, including Mr Jawar, who then returned home to set up the OMN’s headquarters in Addis Ababa as the voice of the “Qeerroo”.

Mr Jawar’s support for Mr Abiy, however, did not last long, as he maintained that self-rule was the key to stability and economic development for all ethnic groups, putting him on a collision course with the prime minister.

For Mr Jawar’s followers, his incarceration last week was further proof that Mr Abiy had betrayed their hopes – especially as his detention had come after much-awaited elections due next month had been indefinitely postponed. Election officials cited the coronavirus outbreak for the postponement.

Jawar quit TV job

Mr Abiy had planned to contest the poll under the banner of his Prosperity Party, which he launched last year by getting eight ethnically-based parties to rally behind his “coming together” vision.

In contrast, Mr Jawar joined the opposition Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC), and stepped down as the chief executive of the OMN’s television station.

The OFC had planned to form an alliance with the OLF and the Oromo National Party (ONP) to contest the election on what was expected to be a strong ethno-nationalist ticket, threatening Mr Abiy’s support among Oromos in the ethnic group’s heartland of Oromia.

Following the postponement of the poll, Mr Jawar warned Mr Abiy that he would be an “illegitimate” prime minister once the term of the current parliament ended at the end of September.

Now, Mr Jawar finds himself incarcerated, with his party saying that both his lawyer and family had been denied access to him, and that he had embarked on a hunger strike.

Abiy’s book burnt

For their part, police say they are pressing ahead with investigations to put Mr Jawar on trial for the murder of an officer allegedly shot by one of his bodyguards during protests which broke out last week in Addis Ababa following the killing of Hachalu – a musician who often sang about the Oromo’s struggle for freedom.

Mr Jawar’s supporters said the policeman was killed by another officer, following a disagreement within their ranks over whether the opposition politician should be arrested.

Police said Mr Jawar would also be prosecuted over protests that led to the deaths of 97 people last October after the politician released a video, alleging that the government was endangering his life by ordering the removal of his security detail.

The allegation – which police denied at the time – triggered a wave of protests that saw some of Mr Jawar’s supporters burn copies of a book that Mr Abiy had published, outlining his “coming together” vision.

While Mr Jawar denied inciting violence, the incident was seen as an attempt to embarrass the prime minister soon after he had won the Nobel Peace Prize for ending a border war with Ethiopia and for his efforts to democratise Ethiopia.

Police also raided the offices of the OMN in Addis Ababa last week, forcing its television station to once again start broadcasting from the US.

Whether Mr Abiy can now regain the political initiative – or whether Mr Mohammed’s detention galvanises the “Qeerroo” to step up their opposition to him – will become clear in the months ahead, leaving many Ethiopians anxious about the future.